"For the country at the center of the crisis to draw €20 billion ($27.77 billion) of foreign demand for a five-year bond yielding under 5% shows that the market now believes Greece will stay in the euro zone, that it won't collapse into chaos and that any further debt relief will be provided by official rather than private lenders."

In fact, it is hard to understand the present turnaround in Greek financial fortunes outside of the context of (i) the widespread belief that the ECB will eventually be forced into a sovereign bond buying QE programme; and (ii) the agreement by the country's Euro Area partners (pressurized by the IMF - see this post) to meet any shortfall on the country's debt reduction programme over and above 110% in 2022 provided it fulfills ongoing EU Commission reform requirements. Following publicaton of the latest EU report in April the FT put it like this:

Under a hard-fought deal reached in November 2012, Greece’s lenders agreed to provide additional debt relief after Athens achieved a primary budget surplus – which excludes interest payments. Jeroen Dijsselbloem, head of the eurogroup of finance ministers, said these talks were set to begin after the summer. The EU official declined to speculate on how eurozone governments would help to lower Greece’s debt levels, insisting this discussion was not part of the just-completed review.What this basically means is that the Greek headline Eurostat sovereign debt figure of 175% of GDP is a very misleading one. 40% of this debt is in the hands of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) on very favourable terms - capital repayments are not due for 25 years while interest payments have a waver till 2023. As Klaus Regling, head of the (ESM) put it in an interview with the Greek newspaper To Vima, "There's no debt sustainability problem for the next 10 years. This is very good news for investors."

Greece's public debt currently stands at about 320 billion euros, or 175 percent of GDP. About 80 percent of it is in the hands of the European Union and the International Monetary Fund, at very low interest rates and on a long repayment schedule.

Regling's ESM, which holds about 40 percent of Greece's debt, is charging Athens about 1.5 percent to cover its own financing costs. ESM rescue loans to Greece have a 25-year repayment schedule and Athens starts paying interest on them 10 years after they are disbursed. The EU and the IMF have so far extended 218 billion euros of bailout loans to Greece over the past four years and Athens stands to get 19 billion euros more by the end of the year.In other words, investors, irrespective of whether or not the ECB introduce QE, can safely buy new Greek debt without worrying too much about whether they are going to be paid back. Between now and 2023 there is no real problem in that department given the de facto Euro Partners guarantee. As I point out elsewhere (On The Trail of Italian Debt) Greek and Portuguese sovereign debt issues are comparatively small beer, and will not threaten the common currency, but the same cannot be said for Italian, or ultimately Spanish, debt. So Greek debt, even at current interest rates looks, frankly, attractive. Doesn't Mario Draghi constantly advise investors not to underestimate the determination of EU politicians to hold the Euro together. Well, there you are.

Real Economy Hits Bottom But Muted Rebound Ahead

Life is rather different, though, within the typical Greek "oikos" (or household). While Greece's economic slump is now hitting the bottom and while, following a pattern seen elsewhere on the periphery, there has been a great boost for the financial sector, there has been relatively little in the way of real gains for the country's hard pressed population at large. Bond yields have fallen sharply, shares are up (or here), and banks are even able to sell bonds (for an example of what they then do with the money see this NYT piece from Landon Thomas), but little of this has trickled through to participants in the real economy.

The economy was down by 1.1% in the first three months of the year when compared with 2013, the lowest inter-annual Q1 drop since 2010. The economy is now something like 25% than it was at the q1 peak in 2009. Since the Greek statistics office STILL don't produce quarterly seasonably adjusted data (is that a measure of the progress they have made?) we don't know for sure, but it does look like the economy actually grew from December to March on an sa basis.

But there is little improvement visible in either retail sales or industrial output.

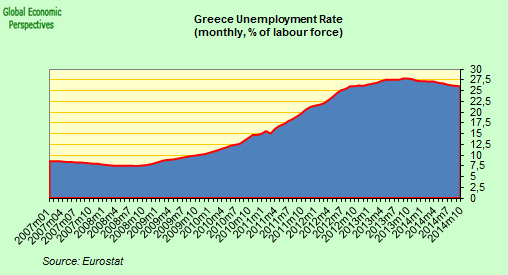

Unemployment has clearly peaked, but so far only fallen marginally.

A lot of the external correction has now taken place, and the current account balance was positive in 2013.

Exports turned positive on a year on year basis in March, but the country country still runs a sizeable goods trade deficit.

Credit gowth remains negative.

So, it is important to bear constantly in mind that the fact the economy has stopped contracting is not at all the same thing as it returning to growth. On that front we will need to wait and see, but there is little that is especially encouraging to date. The problem with having the Euro as a currency was never how to stop the economy contracting. It was always the difficulty which would exist in subsequently returning the economy to growth. Italy and Portugal pre-crisis didn't see their economies shrink, but they did remain stuck in low growth.

The most serious problem facing Greece right now is evidently deflation.

Inter-annual inflation has now been negative for 14 months. Curiously, in the Greek case the main problem with deflation is not going to be that debt levels are pushed up, since as we have seen above excess Greek debt is now effectively guaranteed by the Euro Area partners. A deflationary debt spiral this isn't likely to become the problem it could be in non-debt-guaranteed countries like Spain or Italy.

Deflation will, most likely, push up the level of non performing loans in banks, but even these can be recapitalized and some of the cost passed on to the common currency partners. The real problem in the Greek case is that people will constantly feel that the amount of money in their pockets is shrinking, which it will be (turnover can be down while sales volume is up). This creates a very important mismatch between the positive discourse about economic improvement coming from the government and the official sector generally and the amount of money people see in their tills and wage packets. Naturally, deflation in this sense is not conducive to political stability, and it is here the main risk to the Greek recovery is to be found. In the meantime, a two tier Euro divided between those who have acquired some sort of implicit debt guarantee and those who haven't has effectively been created, yet few have so far seen fit to notice the fact. As the IMF stated in their latest (eleventh) Portugal Program Review:

"While staff considers public debt to be sustainable over the medium term, this cannot be asserted with high probability. However, systemic risk from contagion to other vulnerable euro area countries, should the sovereign fail to service its debt, continues to justify exceptional access......Nevertheless, commitments by euro area leaders to support Portugal until full market access is regained—provided the authorities persevere with strict program implementation—give additional assurances that financing will be available to repay the Fund".

.png)