One thing we've learned as the euro crisis has unfolded is that the enthusiasm of experts in London and New York for offering advice to the struggling countries on Europe's periphery is matched only by their passion for awkward neologisms. The world was just getting used to "Grexit" (Get it? A Greek exit from the euro!) when "Spexit" began to rear its ugly head in the financial press.

Naturally, the events of recent days have brought Spain back to the forefront of the debt crisis, generating insecurity about the reliability of the official fiscal deficit numbers, the validity of central bank statistics, and new numbers showing capital flight reaching alarming levels. Only this week, Spain announced that the central bank governor, Miguel Angel Fernandez Ordoñez, will be leaving early as part of a government effort to restore its credibility. Some are now anticipating that Spain's exit from the eurozone will come before Greece's departure.

I would hope that those clamoring for these countries to go their own way are at least better intentioned than they are informed, since normally they exhibit a singular lack of understanding about how political systems in southern and eastern Europe actually work.

It is now essentially conventional wisdom in the British and American press that Greece needs to return to the drachma. British journalists are even racing to hunt down the London printing works that have supposedly been given the contract to print New Drachmas, the putative local replacement for the euro. The only snag is, according to all opinion polls, the Greeks themselves are not happy with the euro but have no interest in dropping it. (Perhaps the perfect Solomonic solution here would be to have the New Drachma introduced as a non-convertible currency for use only within Fleet Street bars and the boundaries of the City of London.)

The Greeks, naturally, are tired of austerity, and of a stupid EU/IMF bailout plan that has only served to totally collapse their economy, explode their debt, and destroy what semblance of external reputation Greek companies had. The Greeks are tired of austerity in the way many in the United States have tired of fiscal stimulus in the run-up to the next presidential election. But no one would suggest that this weariness is an indication that Americans want to drop the dollar.

As an economist, I have always argued that the common currency was a mistake. I am a "euro" skeptic, but not a "Euroskeptic," and I think it important that people outside Europe understand that this distinction exists. There is no doubt that the euro, like Dr. Stangelove's doomsday machine, is an infernal device destined to blow up one day, but also so designed that any attempt to dismantle it simply detonates the bomb. This is why, tired as they may be, those who live on Europe's southern fringe have little appetite for leaving or taking part in yet another experimental new currency order. Better put, they have little appetite for leaving in a disorderly fashion. And disorderly the leaving would have to be, since if core Europe has little appetite for assuming the cost of keeping the eurozone together, it will surely have even less for paying the much larger bill associated with exit and default.

The media's increasing scrutiny of Spain is similarly misguided. Despite the many voices now recommending a "Spexit," few are really knowledgeable about daily life here in Spain, and even fewer are actually to be found inside the country.

The story of how Spain got to this point is well-known. There was a huge property bubble (could we say the mother of all of them?), a decade of above-EU-average inflation, a massive loss of competitiveness, a huge current account deficit, and an unprecedented stock of external debt. All of this now needs to be unwound, but here's the rub: It is very easy to structurally distort an economy within the framework of a currency union, but very difficult to correct the distortions once generated. This is why so many rightly say that in Spain it is all pain as far ahead as the eye can see. It is not that the Spanish people like this, but just that they don't see any clear and better alternative. And indeed, while only 37 percent of Spaniards believe having the euro is a good thing, according to a recent Pew poll, 60 percent favor keeping it.

The departure of Ordoñez, the central banker, may seem more dramatic from the outside than it does from within. Certainly Mafo, as he is called, bears a heavy responsibility for Spain's continual failure to get a grip on the rot in its financial system, and for the disastrous decision to allow the insolvent Bankia conglomerate to go to IPO last year, losing shareholders more than $2 billion and badly damaging the credibility of the country's banking sector. But his is only one name on what should be a very long list of putative villains, including members of the present government, the previous one, the EU Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB), and last but not least the IMF, where ex-Bank of Spain deputy director Jose Viñals has been busying himself for months writing reports suggesting the condition of Spain's banks was not all that bad.

The real question is what happens next. Spain, like the euro itself, is both too big to rescue and too big to fail. Spain's banks need capital from the government, but the government itself can't finance them. Foreign investors are leaving in droves, but no matter how many liquidity offers they get from the ECB, the country's banks simply can't buy all the debt. So the country needs European (read: German) money. The problem is that if this takes the form of an injection of bank equity, then Germany could end up all but owning Spain's banks, which would expose German taxpayers to considerable potential losses should the situation deteriorate further. At this point Berlin could firmly put its foot down, and we will have another impasse.

At the end of June, Europe will face what many consider to be a perfect storm: results of the Greek elections and details of the new, independent, Spanish bank valuations, which are sure to find that significantly more money will be needed for recapitalization. This will undoubtedly be a make-or-break moment in the ongoing debt crisis, and, if things were to spiral hopelessly out of control, a Spexit could become a real possibility. My advice to all those external well-wishers would be: Be careful what you ask for, since you might not like what you finally get.

This article originally appeared in the magazine Foreign Policy.

Greek Data Updates

Edward Hugh is only able to update this blog from time to time, but he does run a lively Twitter account with plenty of Greece related comment. He also maintains a collection of constantly updated Greece data charts with short updates on a Storify dedicated page Is Greece's Economic Recovery Now in Ruins?

Thursday, May 31, 2012

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Can This Really Be Europe We Are Talking About?

In recent days I have been think a lot, and reading a lot, about the implications of Greece's recent election results.

At the end of the day the only difference this whole process makes to the ultimate outcome may turn out to be one of timing. If Alexis Tsipras of the anti bailout, anti Troika, party Syriza won and started to form a government then the second bailout money would undoubtedly be immediately stopped. On the other hand if the centre right New Democracy wins and is able to form a government, as the latest polls tend to suggest, then the country would quite possibly try to conform to the bailout conditions, but in trying it would almost certainly fail, and then the money would be stopped. Before the last election results, it will be remembered, this was the main scenario prevailing.

Indeed reports coming out of Greece suggest that the end point may be reached more quickly than even previously thought, since the main impact of recent events is that the reform process in the country has been put on hold, meaning that slippage on implementation by the time we get to June will be even greater than it otherwise would have been.

Grexit Ahoy?

Either way, it is what happens next that leads to all the speculation. The international press has been full all though the last week of statements from one European leader after another suggesting that Greece may need to exit the Euro. The latest to add his name has been the Slovenian Finance Minister Janez Sustersic, but before him there has been a long list of leading personalities including EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht who told the press that the European Commission and the European Central Bank were working on scenarios in case the country had to leave. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi even entered what are unchartered waters for the institution he leads and acknowledged that Greece could end up leaving the euro area, although if it did he stressed the decision would not be taken by the ECB.

In The Name Of God Go!

While Mario Draghi may have been being strongly diplomatic, ECB Executive Board member Joerg Asmussen was far less so, and told Handelsblatt newspaper on May 8 that if Greece wanted to remain in the euro, it had “no alternative” than to stick to its agreed consolidation program. The influential German magazine Der Spiegel went even further. Under the header "Time To Admit Defeat, Greece Can No Longer Delay Eurozone Exit", the magazine said what had previously been the unsayable: "After Greek voters rejected austerity in last week's election, plunging the country into a political crisis, Europe has been searching for a Plan B for Greece. It's time to admit that the EU/IMF rescue plan has failed. Greece's best hopes now lie in a return to the drachma".

The inconvenient problem is that things don't look that way in Athens, where even the anti-establishment Alexis Tsipras is only talking about ending austerity, and renegotiating agreements, at the same time making it abundantly clear he has every intention of staying in the Euro. The fact of the matter is that there are very few Greeks who actually want to leave, and it is hard to believe that those arguing the country's best hopes are either this, or that, really have the true interest of the country and its citizens at heart. The FT's John Dizard sums the situation up thus: "There has been an astonishing quantity of nonsense written in the past couple of weeks about the prospect of “Grexit”, or Greece's exit from the Euro".

One of the key additional reasons that much of what has been written has been "nonesense" is that few have stopped to think about what the real cost to core Europe would be of a Greek default (see below). But then, they never have been that strong on financial arithmetic in Berlin.

So whether push comes to shove at the next review, or the one after, no one is really clear what gets to happen next, and this is part of the reason why there is so much nervousness in the markets at this point. Many assume that after the tap is turned off the country would quickly run out of money, but there are a variety of devices that the Greek government, in conjunction with the central bank, could use to keep the cash flowing. Some think the country would follow the Argentinian example, and start issuing internally valid scrip money, like the ill fated Patacos or Lecops. But Argentina was not in a currency union with the United States, the country had simply unilaterally decided to peg the Peso to the Dollar. Argentina could not print Dollars, but Greece can - in a variety of ways, the best known being Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) - generate its own Euros, and enable the government to, for example, sell T Bills to Greek banks in order to pay pensioners, civil servants, government suppliers etc.

Then, so the story goes, the ECB would have no alternative but to shut Greece off from the Eurosystem. To some this might seem like an act of war. This wouldn't be Greece leaving, this would be Greece being turfed out. Yet this secnario was just what the markets got a scare about this week, when the ECB announced it was cutting off liquidity to four Greek banks. Ominous echoes of Mr Draghi's words about the ECB protecting the integrity of its balance sheet. As it turns out, the move was less sinister than it seemed, since part of the problem was that the Greek government bureaucracy was inefficiently holding up the recapitalisation of some Greek banks, a move which had left them with negative capital, and the ECB was understandably reluctant to continue accepting collateral from them under these circumstances. Part of the problem here is that very few people, as FT Alphaville's Joseph Cotterill points out, really understand what ELA is, but this is not really surprising as the ECB itself has hardly been forthcoming with information and details on how ELA is being used.

In any event, continuing the supply of liquidity to Greek banks, and including or excluding the Greek central bank in/from the Eurosystem are likely to become key issues as we proceed. As Mr Draghi argues the issue is a political one, not a banking one, which means the bank is going to be very constrained if it wants to act as a bank without the relevant authority. This is the kind of hot potato which is likely to be passed from one desk to the next (Yes, Mr President, but...) with no one really being willing to go down in history as the person who might have torn Europe apart, which leads us to the conclusion that the "muddle through and fudge" stage might last quite a bit longer than many are expecting.

If I Owe You 10 billion I have A Problem, But If I Owe You 300 billion..........

As John Paul Getty famously said, "If you owe the bank $100 that's your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that's the bank's problem". Never a truer word was said in the Greek case, and it is the reality that Mr Tsipras and those around him have, I suspect, understood. Now I fully appreciate that the Troika are a group of people who are motivated largely by principles not by money, but when your principles could cost you, and those providing you with the money you spend, 200 billion Euros, 300 billion Euros, or whatever, then dare I suggest there is food for them to think.

Estimates of just how much the Troika are on the hook for should Greece default vary, but a common number is somewhere in the 200 billion euro range. Of course, some of this would eventually be recoverable, one day, and assuming Greece were able to pay, but in the meantime (given the super senior status of the IMF participation) it is highly likely that governments and taxpayers in the other Euro Area countries would need to cover the shortfall, and this, to put it mildly, is unlikely to be popular with voters. Yet another reason for "fudge and muddle through".

There are three main sources of Troika exposure to Greece, bailout loans, sovereign bonds owned by the ECB, and liquidity provided to the Greek central bank thorugh the Eurosystem via what is known as Target2. Now according to estimates by Commerzbank analyst Christoph Weil, between loans and bond purchases Greece owes a total of €194bn, which breaks down into €22bn owed to the IMF, €53bn to Euro Area countries, €74bn to the EFSF and €45bn to the ECB. On top of this there are Target2 liabilities of the Greek central bank vis-à-vis the ECB - and indirectly to the German banks - to the tune of €104bn.

As Christoph says in his report: "It would undoubtedly be bitter for the German government to have to tell taxpayers they would have to fork out €75bn if the debts were not repaid, but the alternative of continuing to throw good money after bad, would not make it any more popular either". Methinks he is being a bit too blasé here, since while it is surely the case that a 75 billion Euro bill for the German taxpayer would cause a furore, I'm not sure he has grasped just what a problem this would then present for continuing with further bailouts as needed with other troubled countries.

Can This Really Be Europe?

Nonetheless, despite the fact that Mr Tsipras would now appear to have Germany's leadership by the short and curlies (something Barack Obama's US advisers will surely have been spelling out to them in Camp David this weekend), it is not at all clear what turn events will take from here on in. History is, after all, often more about the unintended consequences of unexpected accidents than it is about plans.

Nevertheless, several things are clear. In the first place, the Greek economy is in unremitting decline, under the weight of the healing measures being applied by the IMF and its European partners. GDP was down by approximately 17% at the end of 2011 from its Q3 2008 high. Not as steep as the Latvian 25% fall - but then the IMF are still forecasting a further 5% decline in 2012, and without devaluation don't expect any sharp bounce back. Both reputationally and infrastructurally the country is being quite literally destroyed. The medicine has evidently been worse than the illness, and maybe it is just coincidental, but the Marshall Plan type aid which the country now obviously needs was originally applied in Europe following the destruction of WWII.

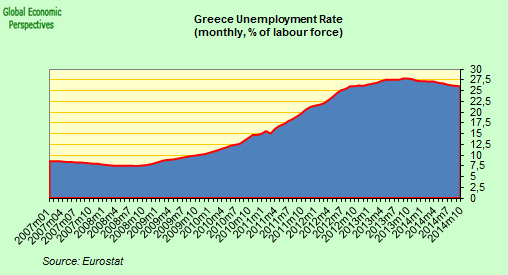

But in Greece it's going to be worse, since no one back then had the kind of ageing population problems the country is now about to face. And while the problem remains awaiting resolution, industrial output and retail sales continue in what has all the appearance of terminal decline, while unemployment - which hit 21.7% in January, second only in the EU to Spain - is still on the rise.

So something patently isn't working, and excuse me for saying it, but I find it hard to think of a leading applied macroeconomist who wasn't warning about this right from the start. But no, the creed of the the micro people and their structural reforms (which, as I keep stressing, are needed) was preferred, and we have ended up where we have ended up.

Right now there are two, and only two, options on the table as far as I can see: help Greece with an orderly exit from the Euro (and crystallise the losses in Berlin, Washington, etc), or print money at the ECB to send a monthly paycheck to all those Greek unemployed. This latter suggestion may seem ridiculous (then go for the former), but so is talk of printing to fuel inflation in Germany (go tell that old wives tale to the marines). If Greece isn't allowed to devalue, then some device must be found to subsidise Greek labour costs and encourage inbound investment - and remember, given the reputational damage inflicted on the country this is going to be hard, very hard, work.

In fact, as I jokingly suggested on my Facebook (and this is a joke, really) on one reading you could come to the conclusion that what lies behind Paul Krugman's recent tantalising play on the association between Wagner (Eurodammerung) and Coppola (Apocalypse Fairly Soon), is Ben Bernanke's idea of a helicopter drop.

Could it be that the message he was trying to subliminally sneak in to camp David this weekend was that unable to afford either Greek exit (colloquially known as Grexit) or Greek Euro Membership, the world's leaders now find themselves trapped in a Gregory Bateson-type double bind. According to Wikpedia "a double bind is an emotionally distressing dilemma in communication in which an individual (or group) receives two or more conflicting messages, in which one message negates the other. This creates a situation in which a successful response to one message results in a failed response to the other (and vice versa), so that the person will be automatically wrong regardless of response. The double bind occurs when the person cannot confront the inherent dilemma, and therefore cannot resolve it or opt out of the situation".

The only viable way to cut the gordian knot without confronting and resolving the underlying problem which at the end of the day afflicts many of the countries on Europe's periphery (devaluation and aided default) would be the organising of weekly helicopter drops of freshly printed Euros all along the beaches of southern Europe (oh, we will fight this one on the beaches, and in the chiringuitos, Mr Tsipras told a shocked group of assembled journalists) at a stroke resolving a large part of the youth unemployment problem, and generating demand for products from core Europe (after all, who would go and work in a dreary old factory when you can get the same income lying on the beach). I can just here them over at the ECB, "whohay, am I on a roll man!", as the printing presses go to work.

And to cap it all, I can just see Paul requesting to fly one of the choppers. "The surfing looks pretty good down there at the moment, Mr President". As one commentor said, you can just smell those Euros burning through the morning mist.

But of course, joking apart, Krugman does have a point. The G8 leaders are now in a ridiculous situation, one they should never have put themselves in. Apart from the cost of disorderly Greek exit, just imagine how Spanish or Italian deposit holders would react to the sight of Greek Euros being forcibly converted into New Drachma, or some such.

Then there is the Guardian's Julia Kollewe, who last week spelt out for us a number of highly unpleasant consquences which would follow, including a rush for the door by a lot of young Greeks. Kollewe indeed paints a bleak picture of Europe's future:

So I ask myself, is this Europe we are talking about here, or is this some kind of dream I am having? Is this where all those high minded ideals of a European Community have lead us, to a Greece where the young people get locked in, like in the old days of the USSR, or locked out as in the days before Schengen. Is this what the real outcome of the election of Francoise Hollande as President of France is going to mean? I hope not, since if it is it would surely split Europe right down the middle, and not just by drawing a line running from East to West.

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog "Don't Shoot The Messenger".

At the end of the day the only difference this whole process makes to the ultimate outcome may turn out to be one of timing. If Alexis Tsipras of the anti bailout, anti Troika, party Syriza won and started to form a government then the second bailout money would undoubtedly be immediately stopped. On the other hand if the centre right New Democracy wins and is able to form a government, as the latest polls tend to suggest, then the country would quite possibly try to conform to the bailout conditions, but in trying it would almost certainly fail, and then the money would be stopped. Before the last election results, it will be remembered, this was the main scenario prevailing.

Indeed reports coming out of Greece suggest that the end point may be reached more quickly than even previously thought, since the main impact of recent events is that the reform process in the country has been put on hold, meaning that slippage on implementation by the time we get to June will be even greater than it otherwise would have been.

"The only thing we are doing is waiting," said a government official who declined to be named. Another Greek official close to bailout negotiations said ministers in the outgoing cabinet have not been authorised to negotiate with Greece's lenders since the May 6 election. A senior party official said the caretaker government would not publish any decrees and all tender procedures were suspended.Looking at the above list, it is hard not to come to the conclusion that it might be in the interests of all concerned for Syriza to win the elections and force the issue. Putting together another weak government that can't implement will only lead to more fudging, and put us back where we are now in three or six months time.

Even before the May 6 election, many reforms were put on the backburner to avoid antagonising voters, officials involved in bailout talks say. These include a plan to slash spending by over 11.5 billion euros in 2013-2014, which Greece must agree by late June to meet a key bailout target.

Other measures Greece should have taken by the end of June include a plan to improve tax collection by 1.5 percent of GDP in 2013-2014, a review of social spending to identify 1 percent of GDP in savings, and a pay cut for some public sector jobs by an average of 12 percent.

One key measure is the budget deficit. Athens was broadly on track in the first quarter with a primary surplus on a cash basis of 2.3 billion euros excluding interest payments on debt, versus a 0.5 billion primary surplus in the same period in 2011.

But low value added tax collection and increased transfers to the social security system to offset weak business and employee contributions continue to be soft spots.

Another problem - which the EU and IMF will check before giving any green light on the accounts - is government arrears. Unpaid debts to third parties for over 90 days stood at 6.3 billion euros at end-March or 3.1 percent of projected GDP this year, according to economists at EFG Eurobank.

EU and IMF policymakers, exasperated by repeated delays on all reform areas over the two years of a first, 110-billion euro bailout, have warned they will not deliver any more aid under the new bailout if Athens veers off the reform track yet again.

Grexit Ahoy?

Either way, it is what happens next that leads to all the speculation. The international press has been full all though the last week of statements from one European leader after another suggesting that Greece may need to exit the Euro. The latest to add his name has been the Slovenian Finance Minister Janez Sustersic, but before him there has been a long list of leading personalities including EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht who told the press that the European Commission and the European Central Bank were working on scenarios in case the country had to leave. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi even entered what are unchartered waters for the institution he leads and acknowledged that Greece could end up leaving the euro area, although if it did he stressed the decision would not be taken by the ECB.

While the bank’s “strong preference” is that Greece stays in the euro area, “the ECB will continue to comply with the mandate of keeping price stability over the medium term in line with treaty provisions and preserving the integrity of our balance sheet,” Draghi said in a speech in Frankfurt today. Since the euro’s founding treaty does not envisage a member state leaving the monetary union, “this is not a matter for the Governing Council to decide,” Draghi said.This is all a long long way from the days of "Hotel California", and the Euro as an institution where you can check in but you can't check out, and other such sentiments which typified the Trichet era, which now seems to far behind us. The decision would not be an ECB one, but what if preserving the integrity of the central bank balance sheet implied cutting of the lifeline to Greece's banking system? The decision might then be nominally Greek, but at the end of the day it would have been forced on the country by a proactive ECB.

In The Name Of God Go!

While Mario Draghi may have been being strongly diplomatic, ECB Executive Board member Joerg Asmussen was far less so, and told Handelsblatt newspaper on May 8 that if Greece wanted to remain in the euro, it had “no alternative” than to stick to its agreed consolidation program. The influential German magazine Der Spiegel went even further. Under the header "Time To Admit Defeat, Greece Can No Longer Delay Eurozone Exit", the magazine said what had previously been the unsayable: "After Greek voters rejected austerity in last week's election, plunging the country into a political crisis, Europe has been searching for a Plan B for Greece. It's time to admit that the EU/IMF rescue plan has failed. Greece's best hopes now lie in a return to the drachma".

The inconvenient problem is that things don't look that way in Athens, where even the anti-establishment Alexis Tsipras is only talking about ending austerity, and renegotiating agreements, at the same time making it abundantly clear he has every intention of staying in the Euro. The fact of the matter is that there are very few Greeks who actually want to leave, and it is hard to believe that those arguing the country's best hopes are either this, or that, really have the true interest of the country and its citizens at heart. The FT's John Dizard sums the situation up thus: "There has been an astonishing quantity of nonsense written in the past couple of weeks about the prospect of “Grexit”, or Greece's exit from the Euro".

One of the key additional reasons that much of what has been written has been "nonesense" is that few have stopped to think about what the real cost to core Europe would be of a Greek default (see below). But then, they never have been that strong on financial arithmetic in Berlin.

So whether push comes to shove at the next review, or the one after, no one is really clear what gets to happen next, and this is part of the reason why there is so much nervousness in the markets at this point. Many assume that after the tap is turned off the country would quickly run out of money, but there are a variety of devices that the Greek government, in conjunction with the central bank, could use to keep the cash flowing. Some think the country would follow the Argentinian example, and start issuing internally valid scrip money, like the ill fated Patacos or Lecops. But Argentina was not in a currency union with the United States, the country had simply unilaterally decided to peg the Peso to the Dollar. Argentina could not print Dollars, but Greece can - in a variety of ways, the best known being Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) - generate its own Euros, and enable the government to, for example, sell T Bills to Greek banks in order to pay pensioners, civil servants, government suppliers etc.

Then, so the story goes, the ECB would have no alternative but to shut Greece off from the Eurosystem. To some this might seem like an act of war. This wouldn't be Greece leaving, this would be Greece being turfed out. Yet this secnario was just what the markets got a scare about this week, when the ECB announced it was cutting off liquidity to four Greek banks. Ominous echoes of Mr Draghi's words about the ECB protecting the integrity of its balance sheet. As it turns out, the move was less sinister than it seemed, since part of the problem was that the Greek government bureaucracy was inefficiently holding up the recapitalisation of some Greek banks, a move which had left them with negative capital, and the ECB was understandably reluctant to continue accepting collateral from them under these circumstances. Part of the problem here is that very few people, as FT Alphaville's Joseph Cotterill points out, really understand what ELA is, but this is not really surprising as the ECB itself has hardly been forthcoming with information and details on how ELA is being used.

In any event, continuing the supply of liquidity to Greek banks, and including or excluding the Greek central bank in/from the Eurosystem are likely to become key issues as we proceed. As Mr Draghi argues the issue is a political one, not a banking one, which means the bank is going to be very constrained if it wants to act as a bank without the relevant authority. This is the kind of hot potato which is likely to be passed from one desk to the next (Yes, Mr President, but...) with no one really being willing to go down in history as the person who might have torn Europe apart, which leads us to the conclusion that the "muddle through and fudge" stage might last quite a bit longer than many are expecting.

If I Owe You 10 billion I have A Problem, But If I Owe You 300 billion..........

As John Paul Getty famously said, "If you owe the bank $100 that's your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that's the bank's problem". Never a truer word was said in the Greek case, and it is the reality that Mr Tsipras and those around him have, I suspect, understood. Now I fully appreciate that the Troika are a group of people who are motivated largely by principles not by money, but when your principles could cost you, and those providing you with the money you spend, 200 billion Euros, 300 billion Euros, or whatever, then dare I suggest there is food for them to think.

Estimates of just how much the Troika are on the hook for should Greece default vary, but a common number is somewhere in the 200 billion euro range. Of course, some of this would eventually be recoverable, one day, and assuming Greece were able to pay, but in the meantime (given the super senior status of the IMF participation) it is highly likely that governments and taxpayers in the other Euro Area countries would need to cover the shortfall, and this, to put it mildly, is unlikely to be popular with voters. Yet another reason for "fudge and muddle through".

There are three main sources of Troika exposure to Greece, bailout loans, sovereign bonds owned by the ECB, and liquidity provided to the Greek central bank thorugh the Eurosystem via what is known as Target2. Now according to estimates by Commerzbank analyst Christoph Weil, between loans and bond purchases Greece owes a total of €194bn, which breaks down into €22bn owed to the IMF, €53bn to Euro Area countries, €74bn to the EFSF and €45bn to the ECB. On top of this there are Target2 liabilities of the Greek central bank vis-à-vis the ECB - and indirectly to the German banks - to the tune of €104bn.

As Christoph says in his report: "It would undoubtedly be bitter for the German government to have to tell taxpayers they would have to fork out €75bn if the debts were not repaid, but the alternative of continuing to throw good money after bad, would not make it any more popular either". Methinks he is being a bit too blasé here, since while it is surely the case that a 75 billion Euro bill for the German taxpayer would cause a furore, I'm not sure he has grasped just what a problem this would then present for continuing with further bailouts as needed with other troubled countries.

Can This Really Be Europe?

Nonetheless, despite the fact that Mr Tsipras would now appear to have Germany's leadership by the short and curlies (something Barack Obama's US advisers will surely have been spelling out to them in Camp David this weekend), it is not at all clear what turn events will take from here on in. History is, after all, often more about the unintended consequences of unexpected accidents than it is about plans.

Nevertheless, several things are clear. In the first place, the Greek economy is in unremitting decline, under the weight of the healing measures being applied by the IMF and its European partners. GDP was down by approximately 17% at the end of 2011 from its Q3 2008 high. Not as steep as the Latvian 25% fall - but then the IMF are still forecasting a further 5% decline in 2012, and without devaluation don't expect any sharp bounce back. Both reputationally and infrastructurally the country is being quite literally destroyed. The medicine has evidently been worse than the illness, and maybe it is just coincidental, but the Marshall Plan type aid which the country now obviously needs was originally applied in Europe following the destruction of WWII.

But in Greece it's going to be worse, since no one back then had the kind of ageing population problems the country is now about to face. And while the problem remains awaiting resolution, industrial output and retail sales continue in what has all the appearance of terminal decline, while unemployment - which hit 21.7% in January, second only in the EU to Spain - is still on the rise.

So something patently isn't working, and excuse me for saying it, but I find it hard to think of a leading applied macroeconomist who wasn't warning about this right from the start. But no, the creed of the the micro people and their structural reforms (which, as I keep stressing, are needed) was preferred, and we have ended up where we have ended up.

Right now there are two, and only two, options on the table as far as I can see: help Greece with an orderly exit from the Euro (and crystallise the losses in Berlin, Washington, etc), or print money at the ECB to send a monthly paycheck to all those Greek unemployed. This latter suggestion may seem ridiculous (then go for the former), but so is talk of printing to fuel inflation in Germany (go tell that old wives tale to the marines). If Greece isn't allowed to devalue, then some device must be found to subsidise Greek labour costs and encourage inbound investment - and remember, given the reputational damage inflicted on the country this is going to be hard, very hard, work.

In fact, as I jokingly suggested on my Facebook (and this is a joke, really) on one reading you could come to the conclusion that what lies behind Paul Krugman's recent tantalising play on the association between Wagner (Eurodammerung) and Coppola (Apocalypse Fairly Soon), is Ben Bernanke's idea of a helicopter drop.

Could it be that the message he was trying to subliminally sneak in to camp David this weekend was that unable to afford either Greek exit (colloquially known as Grexit) or Greek Euro Membership, the world's leaders now find themselves trapped in a Gregory Bateson-type double bind. According to Wikpedia "a double bind is an emotionally distressing dilemma in communication in which an individual (or group) receives two or more conflicting messages, in which one message negates the other. This creates a situation in which a successful response to one message results in a failed response to the other (and vice versa), so that the person will be automatically wrong regardless of response. The double bind occurs when the person cannot confront the inherent dilemma, and therefore cannot resolve it or opt out of the situation".

The only viable way to cut the gordian knot without confronting and resolving the underlying problem which at the end of the day afflicts many of the countries on Europe's periphery (devaluation and aided default) would be the organising of weekly helicopter drops of freshly printed Euros all along the beaches of southern Europe (oh, we will fight this one on the beaches, and in the chiringuitos, Mr Tsipras told a shocked group of assembled journalists) at a stroke resolving a large part of the youth unemployment problem, and generating demand for products from core Europe (after all, who would go and work in a dreary old factory when you can get the same income lying on the beach). I can just here them over at the ECB, "whohay, am I on a roll man!", as the printing presses go to work.

And to cap it all, I can just see Paul requesting to fly one of the choppers. "The surfing looks pretty good down there at the moment, Mr President". As one commentor said, you can just smell those Euros burning through the morning mist.

But of course, joking apart, Krugman does have a point. The G8 leaders are now in a ridiculous situation, one they should never have put themselves in. Apart from the cost of disorderly Greek exit, just imagine how Spanish or Italian deposit holders would react to the sight of Greek Euros being forcibly converted into New Drachma, or some such.

Then there is the Guardian's Julia Kollewe, who last week spelt out for us a number of highly unpleasant consquences which would follow, including a rush for the door by a lot of young Greeks. Kollewe indeed paints a bleak picture of Europe's future:

The Argentinian example shows that a Greek debt default and exit from the eurozone are likely to have dire economic and social consequences, at least in the short term. The country will become isolated. With lending drying up and accounts frozen, small businesses will go bust, exports plunge and the country will lurch deeper into recession. "Consumption could drop by 30%," says Nordvig. "There will be some pretty extreme effects."In fact, the last time something like this happened – in Argentina in 2001 – 175,000 Argentinians arrived in Spain alone.

"Mass unemployment is likely, as is an exodus of young skilled workers. If tens of thousands of Greeks headed to the borders, they might even be closed. Greek soldiers patrolling the roads and ports to keep their fellow citizens in? It is not impossible".

So I ask myself, is this Europe we are talking about here, or is this some kind of dream I am having? Is this where all those high minded ideals of a European Community have lead us, to a Greece where the young people get locked in, like in the old days of the USSR, or locked out as in the days before Schengen. Is this what the real outcome of the election of Francoise Hollande as President of France is going to mean? I hope not, since if it is it would surely split Europe right down the middle, and not just by drawing a line running from East to West.

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog "Don't Shoot The Messenger".

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)