The Cost Of Not Finding A Solution

It is now clear that Greece's economy has been going backwards over the last 6 months, and that it has once more fallen back into recession. Greek GDP fell by 0.4% in the last three month of 2014, and by a further 0.2% in the Jan - March 2015 period. As a result at the end of March Greek GDP was only 0.3% above the year-earlier level. This is a lot lower than expected in IMF forecasts, and - perhaps more importantly - well out of line with what is needed to maintain the 2022 debt sustainability targets on which continuing Fund support for Greek programmes depends.

Indeed "Greece is so far off course on its €172bn bailout programme that it faces losing vital International Monetary Fund support unless European lenders write off significant amounts of its sovereign debt", Peter Spiegel wrote in the Financial Times on 4 May 2015. The reason for this is obvious: IMF regulations prevent the Fund continuing to make tranche payments to countries where there is a foreseeable financing shortfall during in the coming twelve months. The worsening in the Greek economic outlook and the consequent reduction in the revenue outlook effectively guarantee this shortfall.

But the sort of debt write-off the IMF is demanding of its European partners goes much deeper than that. Future IMF participation in any new Greek programme after June is also in doubt because without additional pardoning the debt will not be on a sustainable trajectory in terms of the objectives set down and agreed upon in November 2012. So you reach a point where extend and pretend hits the proverbial fan. You can, of course, do more extend and pretend till the next time it happens, but at this point the IMF seems reluctant to do so. On the other hand austerity-type spending cuts which only make the economy smaller and the growth path lower simply don't help in this context, since what they give with one hand (debt reduction) they take away with the other (in the form of lower GDP).

The background to the current stand-off is to be found in the debt targets the Eurogroup agreed with the IMF in November 2012 and which effectively made the current programme possible. Given the latest recession these targets are clearly now not attainable. On the other hand Greece is totally bust, so the only way the negative effects of the negotiating gridlock can be paid for is by someone else "coughing up" (or rather "pardoning" debt). This someone will need to be the Euro partners (who else is there), and the longer the stand-off goes on the higher the cost. Naturally the other alternative would be allowing Grexit, but arguably the cost of Grexit would be much higher to the Euro partners, and by a large multiple.

The issue of the growing IMF/Eurogroup divergence came to general public attention over the weekend when an IMF internal memo was leaked to Channel 4 News (UK). The key point in the memo, which is hardly news, is that Greece is running out of money. “There will be no possibility for the Greek authorities to repay the whole amount unless an agreement is reached with international partners," referring to a series of June repayments to the IMF amounting to roughly 1.5 billion euros.

This impression is also confirmed by details of the letter that the Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras wrote to International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde at the start of May (see details in this Kathimerini article) to inform her that Athens would not be able to pay the 750 million euros due to the Fund on May 12 unless the European Central Bank allowed Greece to issue more T-bills. It appears that at the time of writing the letter (which also went to EU Commission President Jean-Claude Junker and ECB President Mario Draghi) Mr Tsipras was not aware he could temporarily use the 650 million euros held on reserve at the Fund to make the payment, which he subsequently did. It's not unreasonable to assume that it was the IMF itself who advised him on this.

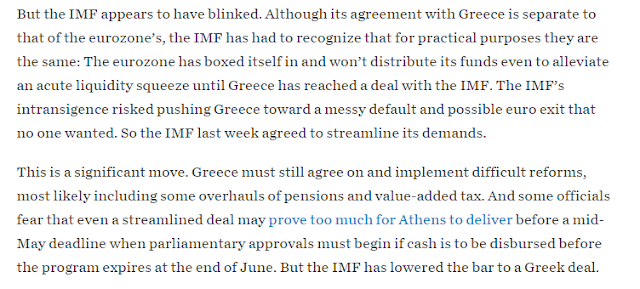

The inter-institutional tensions are evidently reaching a critical stage, although in fact the issue has now been knocking around for some weeks, as Simon Nixon reported in the WSJ on April 22.The IMF, he said, "appears to have blinked".

The general impression being given is that the IMF is contemplating a much lower bar for agreement, and then possibly disengagement from any post June programme. The Euro partners are evidently anxious to avoid this outcome, but they are caught between a rock and a hard place.

On Or Off The Hook?

In order to understand what is going on between the Eurogroup and the IMF it is necessary to go back to a 2013 document entitled: The Third Review Under the Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility (what a mouthful that is, henceforth the Third Review). In particular the following paragraph in that document off a key:

The macroeconomic outlook, debt service to the Fund, and peak access remain broadly unchanged and euro area member states remain committed to an official support package that will help keep debt on the programmed path as long as Greece adheres to program policies. Capacity to repay the Fund thus depends on the authorities’ ability to fully implement an ambitious program. It continues to be the case that if the program went irretrievably off-track and euro area member states did not continue to support Greece, capacity to repay the Fund would likely be insufficient.Now all of this may sound - at least to the uninitiated - like a load of old bureaucratic mumbo-jumbo, but actually there are a number of key statements here which may help to put the current internal Troika tiff in some sort of broader and more intelligible perspective.

The cited paragraph talks about three issues: the macroeconomic outlook, the commitment of euro area member states to support Greece and keep the debt on the programmed path as long as Greece adheres to the programme's requirements. It also warns of the danger that should the programme go "irretrievably off track", and euro area member states not give the necessary support then the country's capacity to repay the Fund would clearly be insufficient - ie the IMF would be left holding the can, and Fund employees would be faced with the complicated task of explaining to its non-European members why losses had been incurred.

Crudely put the position is this - as long as the IMF continue to write reviews stating the Greek programme is on track then the euro area member states are on the hook to cover any shortfall in Greek debt performance in order to make the 2020 and 2022 targets (see above) achievable. This is a commitment they undertook during negotiations on the second bailout agreement.

On the other hand, if the IMF were to start producing reports stating that the programme was off-track because of Greek non-compliance, rather than for example arguing that the numbers were out of whack due to faulty macroeconomic forecasts (and of course the recent economic relapse makes those forecasts even less realistic), then the euro area member states would be off the hook from additional stepping up to the plate with the result that the IMF would end-up taking a loss.

Well the present recession makes it evident that those targets are even less achievable than they were previously, and that future debt sustainability analyses will have to reflect this. Bottom line: the IMF has a clear interest in enabling Greece to sign successfully off the current programme (due to end in 2016) and they thus have more interest in giving the country a "pass" note than the Eurogroup ministers do.This is why, in Simon Nixon's words, they are blinking, to the great discomfort of the Eurogroup partners.

Bottom Line: When You're Bust, You're Bust

A lot of attention is being paid at the moment to the idea that Greece is running out of money, and indeed there is a lot of chuckling about just how much grasp Yannis Varoufakis actually has of game theory. But at the end of the day it is also true that when you have lost everything (in the bankruptcy sense) you have relatively little still to lose. To some extent the idea that the Greek government might be deploying this strategy - known technically as coercive deficiency - was explored by Jacques Sapir back in February. In my humble opinion far too much energy may have been wasted on laughing at Mr Varoufakis (which might precisely have been his intention) and far too little invested in trying to think through what he might have been up to.

If delays in negotiations mean a large bill is run up on your credit card (figuratively speaking) at the end of the day you can't pay it, so someone else will have to. This is the situation Greece is now in. If non performing loans start to rise with the new recession eventually these will have to be written off, and the bank recapitalization costs will go on someone else's account.

The IMF memo in fact draws attention to this issue, and states that “non-performing loans are at very high levels and – going forward – the system might suffer from important stress." Indeed they go further and point out how "staff also noted a dramatic deterioration in the payment culture in the country”. This is what you would expect to find in a country steadily, and day by day, going bankrupt.

It's no longer clear that even if progress was made in the next two weeks towards some sort of fudged compromise deal - the so called "quick and dirty outcome" that the IMF oppose - that this would be able to get the necessary agreement from all EU parties and the IMF before the June payment. That is not necessarily an insurmountable issue, but it does highlight just how near to a potential brink (or "accident") we are, and it also serves to draw attention to the point that the longer all this goes on the greater the cost for Eurogroup members. Reforms will bring a bit more growth, but only in the longer run. Whatever the package of structural reforms the Greeks sign on to it won't do that much to mitigate the effects of the hit the Greek debt sustainability profile just took.

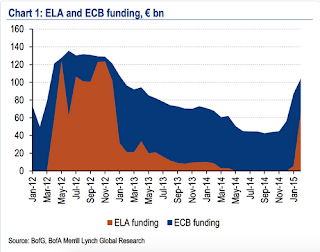

But then there is the other alternative - just allow the momentum of the present impasse to carry Greece straight out of the Euro Area. That would solve the problem of getting a deal, but the cost, when you come to think of EFSF and IMF loans plus ELA would hardly be negligible, not to mention the as yet unquantified geopolitical and contagion effects.

Whatever way you look at it, the next few weeks are certainly likely to be interesting.

.png)